Dear Peter,

Thanks for inviting me to this exchange of ideas. It’s true that we’ve never met, but by all means, let us pretend that we’re old friends writing each other.

In fact, let me use the fact that we’ve never met as a jumping board to dive right in to our debate. I have no recollection of ever having met you, and neither do you. If our paths did cross at some point, it was a chance encounter and we were totally unaware of it.

Can you convince yourself otherwise? Can you simply choose to believe, say, that we’ve had a beer together in Dresden last month, when you gave a talk at the Spring School on Cognitive-Affective Neuroscience there? (Yes, I checked your CV.)

It shouldn’t be too difficult for you to imagine having met me there. You were there, after all. I’m betting you visited some local pub and had some beers there. Just include me in that mental picture (you can tell what I look like by checking the picture above).

I daresay you can’t simply choose to believe this, since you have no reason to think it’s true. You could pretend to believe it, or you could try some self-deception, but I think it wouldn’t work. Suppose someone were to point a gun at you and threaten you: “Believe right now that you had a beer with Maarten Boudry in Dresden last month, or I’ll blow your brains out”. Even with such a strong desire to believe, you wouldn’t be able to oblige.

There are many more examples that show that belief is not under voluntary control. I can’t choose to believe that there is a cup of coffee right in front of me now, because the evidence of my senses is undeniable that, in fact, it’s a cup of tea. I can’t choose to believe that there’s a largest prime number, because I can’t forget about the mathematical proof that there isn’t one.

It’s not just that I can’t believe things that are transparently false or logically impossible. Take the proposition “The number of black holes in the universe is even”. I know that black holes exist, I believe their number is finite, so I know the probability of the total number being even is 50%. Still, in the absence of any reason that tips the balance in favor of ‘even’, I can’t bring myself to believe it. There’s no switch in my brain I can flip.

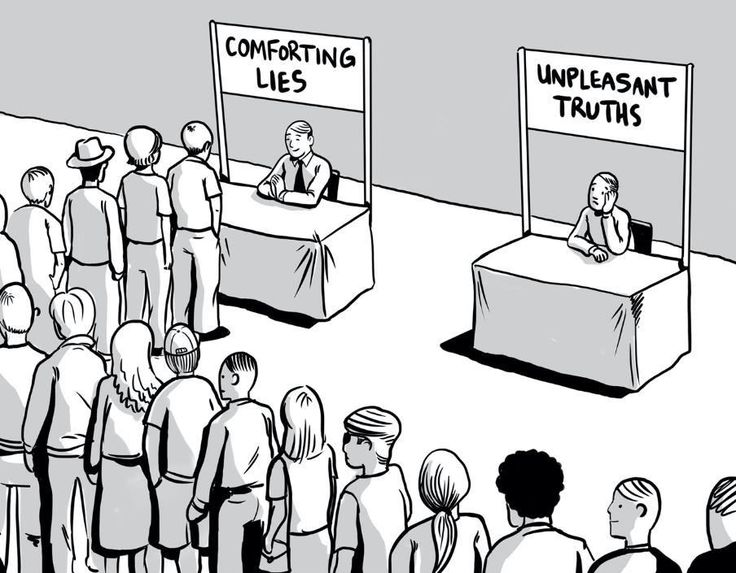

The mental capacity for unrestrained wishful thinking also wouldn’t make much evolutionary sense. If ever there were some hominids who did have this capacity, they probably didn’t live long enough to become our ancestors. Evolution doesn’t care about our sense of comfort. It wants us to pay attention to reality, even (I’d say especially) when reality is terrifying. Do you remember the Joo Janta 200 Super-Chromatic Peril Sensitive Sunglasses from the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy? It’s a nice gizmo: you put them on, and at the first sight of danger, they turn completely opaque. Very relaxing for anxious space travelers! If you don’t see the monster, it can’t hurt you. Wearing these sunglasses wouldn’t be very conducive to your fitness, would it?

Now, I agree that this is not the end of the story. You’re right that we have plenty of anecdotal and scientific evidence that the wish is sometimes the father of the belief. Aesopus’s fox believed he didn’t want the grapes, a grief-stricken mother believes her dead child is waiting for her in heaven, a husband believes his wife is faithful even though everyone knows she’s sleeping with his best friend. So is it true that, at least some of the time, people can simply choose to believe something because it’s comforting to them, alleviating their guilt, boosting their self-esteem?

By and large, I think two conditions need to be fulfilled. First, the available evidence needs to cooperate a little bit. In order to believe that X is true, X needs a have certain ring of plausibility. If the evidence against X is too blatant, overwhelming and/or right in front of your eyes, then you cannot simply choose to believe X anyway (see my example of the cup of tea and the largest prime). A husband can ignore the tantalizing clues that his wife is having an affair, and deceive himself into believing she has always been faithful to him, but his illusion will be permanently shattered if he catches her with her lover in flagrante delicto. The fox can deceive himself that he didn’t desire the grapes behind the fence, since internal psychological states are somewhat ambiguous and open to self-manipulation, but he cannot choose to believe there were no grapes in the first place, since he saw them with his own eyes. There are many cases of people who regret that they are no longer capable of believing something, because they have been exposed to some pretty damning evidence. (“If only I hadn’t opened this e-mail, then I could still believe my husband was not cheating on me!”) Belief in heaven, in that regard, is perfect for wishful thinking. It’s completely unfalsifiable, since heaven is supposed to be in some other invisible dimension (whatever that means), and because no-one has ever come back from beyond the grave to inform us that there is no heaven (or that we’re all going to hell).

The second condition for successful ‘wishful thinking’ is that you should not be aware that you’re about to engage in wishful thinking. A wish can spawn a belief if it’s working its magic just outside your conscious attention. If you’re going straight for your target, it won’t work (“OK, this heaven thing sounds comforting. I really wish it were true. I’m trying now!”). People who behave like Aesopus’s fox usually don’t realize what they’re doing, and typically deny it if someone points it out (“No, really, I didn’t want it anyway. If I wanted to, I totally could’ve had it.”). People like to think of themselves as dispassionate, rational and sensible. No-one likes to think of himself as a dupe who simply believes anything he likes to be true, and even religious believers have to be able to look in the mirror every morning. They need to come up with some sort of reason to believe in the afterlife. Sure, those may be half-baked, far-fetched, harebrained, fallacious reasons, but they are reasons nonetheless. ‘Wishing it were true’ is not a reason to believe something.

Now, you’ll probably point to religious people who candidly admit that they believe in the afterlife only because it’s a comforting thought. I’m as fascinated by those people as you are. But I’d say those people either don’t really believe in the afterlife, or they have other, non-disclosed reasons for believing in the afterlife. I’m not sure, and perhaps you can convince me otherwise, but I think it’s impossible for anyone openly admit: “I believe this is true, but I have no reason to believe so. I just wish it were true, so I believe it”.

Now, have you already persuaded yourself that we had a beer together in Dresden? Remember what a blast that was! We poked fun at postmodernist philosophers and Social Justice Warriors. When we went back to your hotel, we witnessed a stray dog humping another dog in the park, and you made some incisive comments about heteronormativity and rape culture. Don’t you wish it were true?

I hope to see you again soon!

Your old friend,

Maarten